Anne of Green Gables — a Bookbinder’s Perspective

First published in April 1908, Anne of Green Gables has never been out of print. The manuscript was repeatedly rejected and even put away into a hat box until Montgomery submitted it to L.C. Page & Company who accepted the book. Maud signed a restrictive contract that was not in the author’s favour—a contract that gave over all rights to LC Page in return for a 10 percent royalty rate on the wholesale price once more than 1000 copies were sold and held her to a five year right of first refusal clause. In the end, there were a series of bitter lawsuits with her publisher over the rights to her work that eventually ruled in Montgomery’s favour.

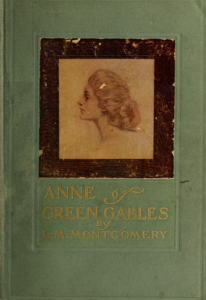

The binding of the first impression of Anne of Green Gables is a typical publishers’ binding of the period. Bound in one of three variants of bookcloth (tan, brown, and green), there is a centered portrait of a young redheaded woman on the cover within a brown frame. The title on the spine and the front board are stamped in gilt. The portrait on the front cover was by illustrator George Gibbs, and the eight interior illustrations were by W.A.J. Claus and M.A. Claus.

Reference photos of the original binding show that it had plain cut edges, a simplified endband, and plain endpapers. Along with gilt titling, there were blind-blocked impressions on both the spine and the front board. It was the typical, full-cloth publishers’ binding.

Publishers’ bindings are so named because they were an innovation of the 19th-20th century, designed to keep up with the vast changes in the printing industry.

Once maligned for their simplicity, publishers’ bindings have been an increasingly interesting area of study for book historians as they herald a shift from intensive handwork to what we now know as the modern book industry.

![]()

“The need for speed, simplicity, and economy in book production led to the introduction of cloth as a binding material and casing as a binding process…. The practice of case binding, in which a book’s cover, or case, is made independently of, even simultaneously with, the textblock and attached to it primarily by adhesion of the endpapers, closely followed the introduction of book cloth. Although casing remained a hand operation until the end of the century, it greatly simplified the binding process and allowed for mass production. The developments of book cloth and case binding, in conjunction with technological advances in the printing industry, led directly to the advent of the publishers’ bookbinding: i.e., a binding designed for and manufactured in quantity for a publisher.”

~ Andrea Reithmayr, Beauty for Commerce:

Publisher’s Bookbindings 1830-1910 ~

![]()

The Image on the Cover

The image of the woman on the cover of the original Anne of Green Gables has an interesting backstory.

According to Montgomery’s diaries, she kept a photograph of a woman by her side for inspiration, while writing Anne of Green Gables. The photograph, as it turned out, was of Evelyn Nesbit.

Taken in 1903 by photographer Rudolf Eickemeyer, Jr, the subject is a young model, Evelyn Nesbit, approximately 18 or 19 years old. The image appeared in Metropolitan Magazine, where Montgomery may have encountered it. (The 30-year history of Metropolitan Magazine (1895-1925) is storied in itself, but at the time this photo was published, the mission of the magazine was to present urban life in New York with a specific appeal to sophisticated theatre-goers, featuring writings from authors such as Rudyard Kipling and Joseph Conrad. Based on her past penchant for magazines of this nature, there is little doubt that Metropolitan Magazine would have greatly appealed to Montgomery.)

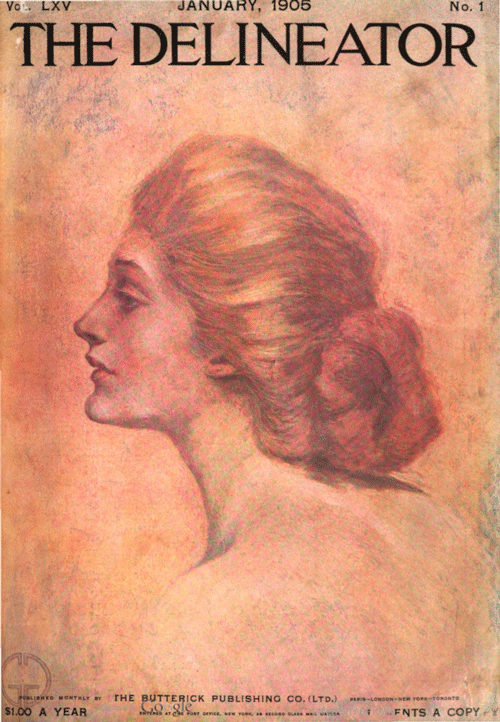

At the time, Evelyn Nesbit was a popular model, and her image appeared in newspapers, magazine advertisements, and other promotional souvenirs of the day, such as sheet music and calendars. Prominent illustrator George Ford Gibbs, known for his illustrations on the covers of publications such as the Saturday Evening Post and The Ladies’ Home Journal, was among the first artists to employ Nesbit as a live model.

Gibbs’s work graced the cover of the January 1905, Vol LXV, No. 1 edition of The Delineator, and it is this very same image that, several years later, would appear on the cover of Anne of Green Gables. The identity of the model George Gibbs used to sketch the cover of The Delineator is uncertain, but this is Gibbs’s work, as evidenced by the GG initials at the bottom left.

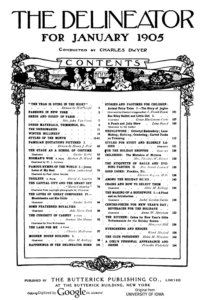

The Delineator, an American women’s magazine by the Butterick publishing company, was a window into the world of the early 1900s. The Table of Contents from that edition is presented on this page. It is a substantial magazine loaded with stories, hymns, and homemaking advice on food, needlework, and fashion.

This glimpse into the popular culture of the time further deepens our understanding of the influences on Montgomery’s work. While we don’t know how the image from the cover of The Delineator truly made its way onto the cover of the L.C. Page & Co’s publication of Anne of Green Gables, there is no mistaking that it was a very fitting snapshot of the world’s (and L.M. Montgomery’s) view of women in 1908.

On one of the last pages of the January 1905 edition of The Delineator, an offer for a copy of the publication cover appears. The offer describes the illustration as a “marvelously beautiful type of the American Girl.” The language used in this advertisement clearly references the artistic styling popularized by another illustrator of the day, Charles Dana Gibson.

C.D. Gibson never used Nesbit as a live model, but he, like other artists of the day, was captivated and included aspects of her likeness in his sketches. However, Gibson’s portrayal of women in general had become the new norm. His illustrations, collectively known as “Gibson Girls” drawings, reflected the “American woman” of the day. His drawings became the feminine ideal and the mirror of society from the 1890s until World War I. Other works from Gibson appear on this page — “A Daughter of the South” and “The Weaker Sex.” It is interesting to note the many parallels between Gibson’s work and the Gibbs illustration used on the cover of Anne of Green Gables.

You can easily see how Maud might have gravitated to the symbolism in these sketches, but it is also important to note the overall influence of Gibson’s work. The Gibson Girl (or, in the words of The Delineator, the “American Girl”) represents a stylish, independent, and self-confident woman who was also tempered by grace. The proliferation of Nesbit’s images, coupled with the popularity of the Gibson Girl, would have influenced Montgomery’s mental image of her new heroine, Anne Shirley, and the red-haired beauty who appeared on the cover of The Delineator in 1905 could readily become the perfect portrayal.

The Delineator was packed with interesting tidbits of the day, including those important puffed sleeves!

![]()

“There in my hand lay the material realization of all the dreams and hopes and ambitions and struggles of my whole conscious existence—my first book! Not a great book at all—but mine, mine, mine,— something to which I had given birth — something which, but for me, would never have existed.”

~ Lucy Maud Montgomery

June 20, 1908 ~

![]()

Evelyn Nesbit 1903

Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 17 Mar. 2012, Wikipedia Image.

Accessed 29 Apr. 2024.

Dwyer, Charles, 1859-, H. F Montgomery, and R. S O’Loughlin. The Delineator. New York [etc.]: E. Butterick & co.; [etc.], retrieved from Hathitrust Digital Library

The Delineator

January 1905 Edition

“A Daughter of the South”

Gibson, Charles Dana, Artist.

A Daughter of the South.

[?] Photograph. Retrieved from the

Library of Congress

“The Weaker Sex”

Gibson, Charles Dana, Artist.

The weaker sex. II.

Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress