Lucy Maud Montgomery and Mental Health

For many years, Lucy Maud Montgomery’s issues with depression and her challenges with caretaking for her mentally ill husband was kept well hidden. In some ways, her most well-known character, Anne – romantic, optimistic, clever, spunky, and resilient – was a shield to the darker threads of Montgomery’s life. It wasn’t until after their death when her journals were published, that the extent of her issues with mental illness became so well known.

![]()

~ “There is no grief like the grief that does not speak.”

Anne’s House of Dreams ~

![]()

Her journals express her pain and anxiety about her husband’s illness, the trajectory of her children’s lives, the bitter lawsuit for the rights to her early books, two World Wars, the death of her stillborn son, the loss of close friends, her ambitions, her depression, her frustrations, and her own complicated sense of self.

Consistent with the medical opinion of the time, both she and her husband were treated by their doctor with barbiturates and bromides, which created an unhealthy dependence. All through adulthood, she suffered from insomnia which exhausted her and coloured her mood.

And though her writing is often seen through the lens of her most optimistic of characters (Anne) – there is still an underlying darkness and ghostliness to some of her stories that speaks to the complexity of sadness and despair. Although she’s often characterized as a post-Romantic’s romantic, there is an underlying thread of the Gothic underneath in such texts as Emily of New Moon and her posthumous collection of stories, Among the Shadows: Tales from the Darker Side.

In 2008, Lucy Maud Montgomery’s granddaughter revealed that the family suspected suicide in her grandmother’s death based on a note of despair found near her bedside. Although this cannot ultimately be known, what was clearly revealed in her journals was an increasing sense of despair. Despair from the caretaking of her husband, despair at the cruelness evident in the world, and the pain of dealing with her insomnia and mood.

![]()

“There was a time when I began the first page of a new volume of this journal with a thrill of excitement. What would be written in it? There were possibilities – hopes – that many of the entries at least would be pleasant. That time has gone. It will never return. I would be content if I could hope that this journal would be free from entries of sadness and worry and disappointment. I cannot even hope that, so crushed and beaten do I feel.”

~ Lucy Maud Montgomery, September 30, 1936 ~

![]()

Mental health, while not openly discussed in her work, remained an ever-present spectre in Montgomery’s life and work. The depth and breadth of her writing over the course of her life is all the more remarkable for what she had to overcome to achieve it.

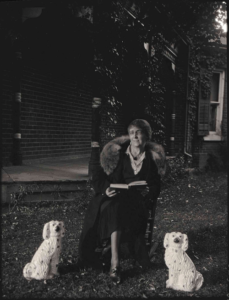

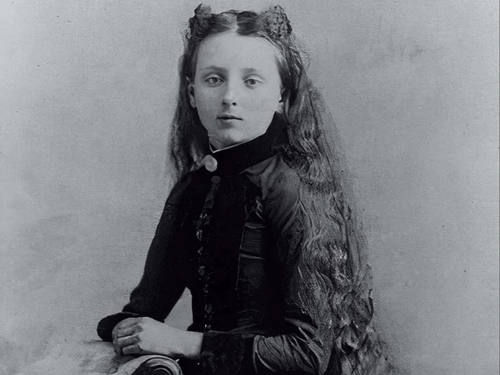

Lucy Maud Montgomery, Age 45-1919

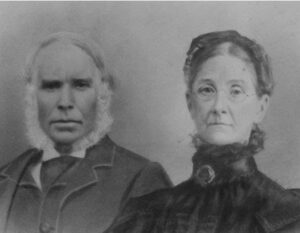

Lucy Maud Montgomery and Ewan in Georgian Bay, Ontario, 1930

Lucy Maud Montgomery in Norval, Ontario, 1932